A lot of different types and sub-types of observation have developed, and now it has the most complex structure of all data collection procedures.

1. Cross-sectional Studies

A cross-sectional study is a type of research that captures information from a population at a single point in time (Figure 1). The information can be obtained from a group of participants with certain characteristics known as variables (e.g. age, gender, origin, education, religion, geographic location, etc). The variables used in a particular study are determined by the research to be carried out, and by the goals of the study. Researchers can use cross-sectional studies to focus on one independent variable, and see how it affects one or more dependent variables. These studies enable researchers to examine several variables at the same time. Cross-sectional studies do not involve the manipulation of variables. They are descriptive studies.

Some examples of cross-sectional studies are given below:

- Descriptive study: conducting market research by collecting data on consumer behaviour within the given period of time with an aim to predict the future trends of consumer behaviour or introduce new sales strategies or launch new products and services. In such a study, the researcher does not analyse the causes, but focuses on the description of the current situation on the market.

- Analytical study: a study examining the lack of calcium in the population of women above 50 years of age. Whereas the focus of the descriptive study would be to determine the level of calcium in women above 50 years of age, the analytical study would focus on examining the factors such as hormonal status, physical activity, nutrition, socio-economic status, education level, etc., in order to explain why some women belonging to such an age group are more likely to develop calcium deficiency than other women, and therefore have a greater probability of developing other illnesses such as osteoporosis.

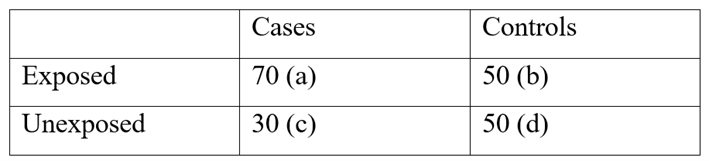

- Case-control Studies: Case-control studies are a type of observational research often used in the fields such as medical research or environmental health. A case-control study is an experimental design that compares two or more groups of participants. One of these groups is the ‘case’ group, and other groups are ’control’ groups. It is important to note that the case group is selected because it is already characterised by the attribute of interest for the study, and the purpose of the control group is to find out if the case group systematically exhibits that attribute more than the control group does. Therefore, by analysing the data collected from the control group, the research hypothesis is either confirmed or rejected. Commonly, tables are used to present data (Table 1).

The risk ratio (or rate ratio) is calculated by using the exposure odds ratio (OR):

- The odds of exposure among cases: OR = a/c,

- The odds of exposure among controls: OR = b/d,

e.g. OR = (axd)/(cxb).

If OR = 1, then the odds of risk is the same for the exposed and non-exposed.

If OR > 1, then the exposure increases the odds of risk.

If OR < 1, then the exposure reduces the odds of risk.

Example: Сase-control study in medicine

The aim of the research was to examine the connection between the contamination of potable water and potental stomack diseases (e.g. gastritis). The case-study group comprised the people diagnosed with a stomach disease, whereas the control group comprised the people without the disease. During the research, the data on the exposure of the participants to the contaminated potable water were collected, with the focus on the variables such as the source of the water, and duration of the exposure, for each group. The aim was to compare the results in order to determine whether there was a correlation between the water contamination and the risk of developing a stomach disease.

Practice tasks:

Researchers are conducting a case-control study of breast cancer using incident cases. The study includes 100 cases and 100 controls. 70% of the cases report smoking. Among the controls, 50% report smoking.

a) Prepare a 2x2 table with the given data.

b) Calculate the exposure odds ratio.

c) Interpret the exposure odds ratio in a sentence.

Answer:

a)

b) Exposure odds ratio = (a/c)/(b/d) = (a*d)/(c*b) = (70*50)/(50*30)=2.33

c) An odds ratio of 2.33 means that the odds of smokers being a case are 2.33 times the odds of non-smokers being a case.