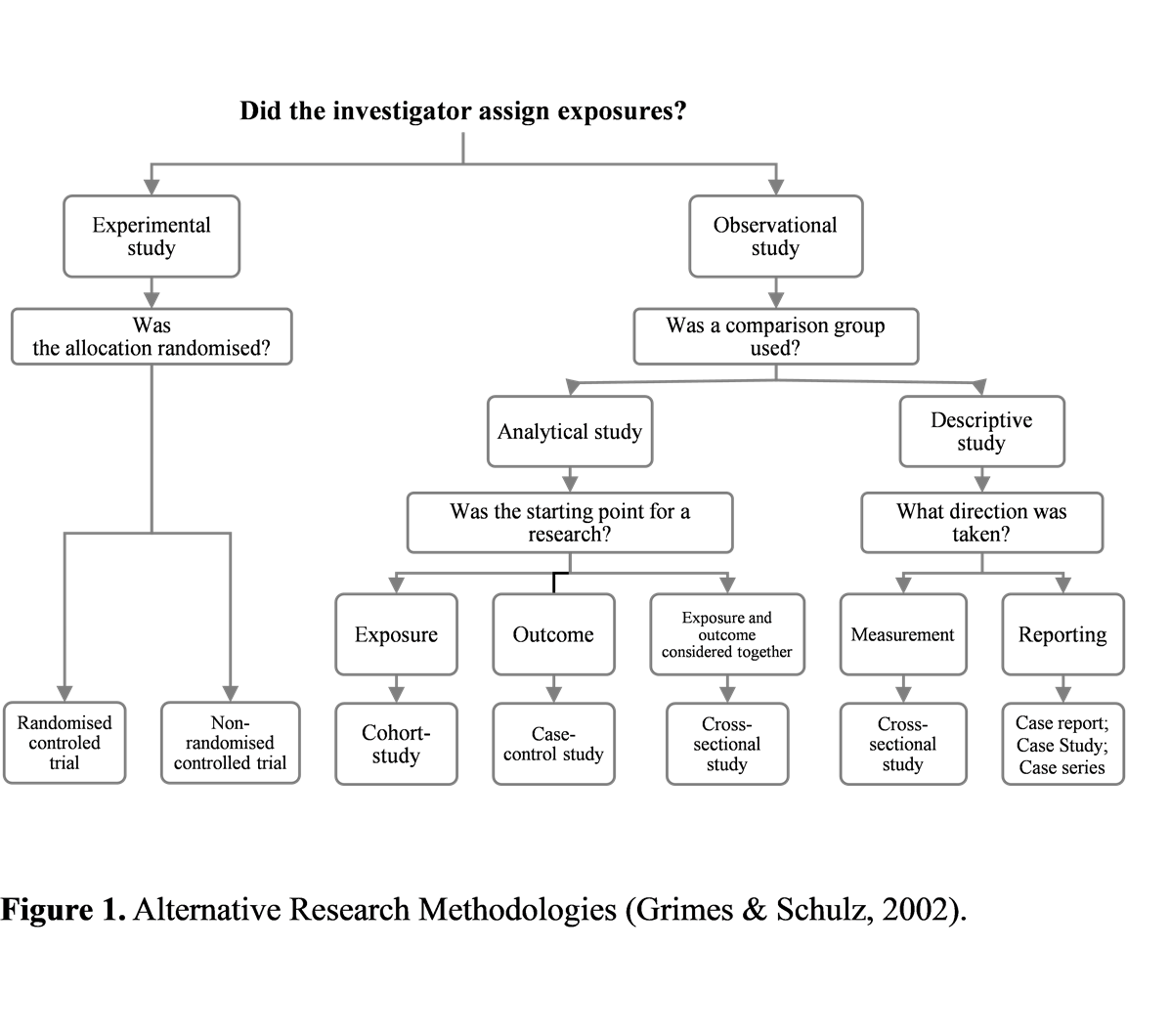

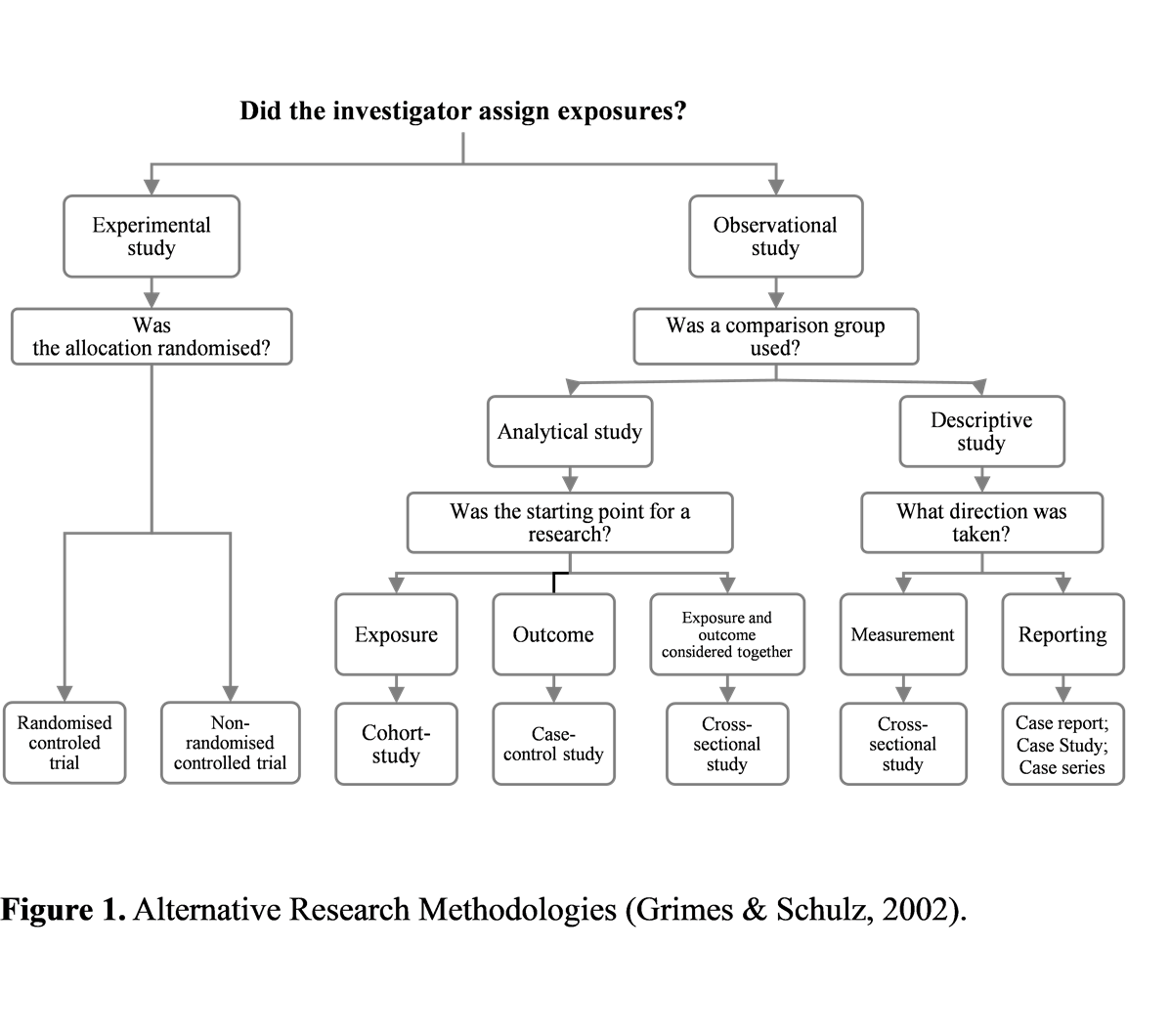

Research can be classified into three main groups based on the application of the research study, its objectives in undertaking the research and how the information is sought (Fig. 1).

What is quantitative research? Quantitative research is a type of research that involves collecting numerical data and analysing it using mathematical methods, particularly statistics. The definition of quantitative research may vary between researchers and educators, but it is generally agreed upon that this approach aims to explain phenomena through numerical data. For instance, (Creswell, 2014; 2018), a proponent of mixed methods, defines quantitative research as a method that explains phenomena by collecting numerical data and analysing it using mathematically based methods.

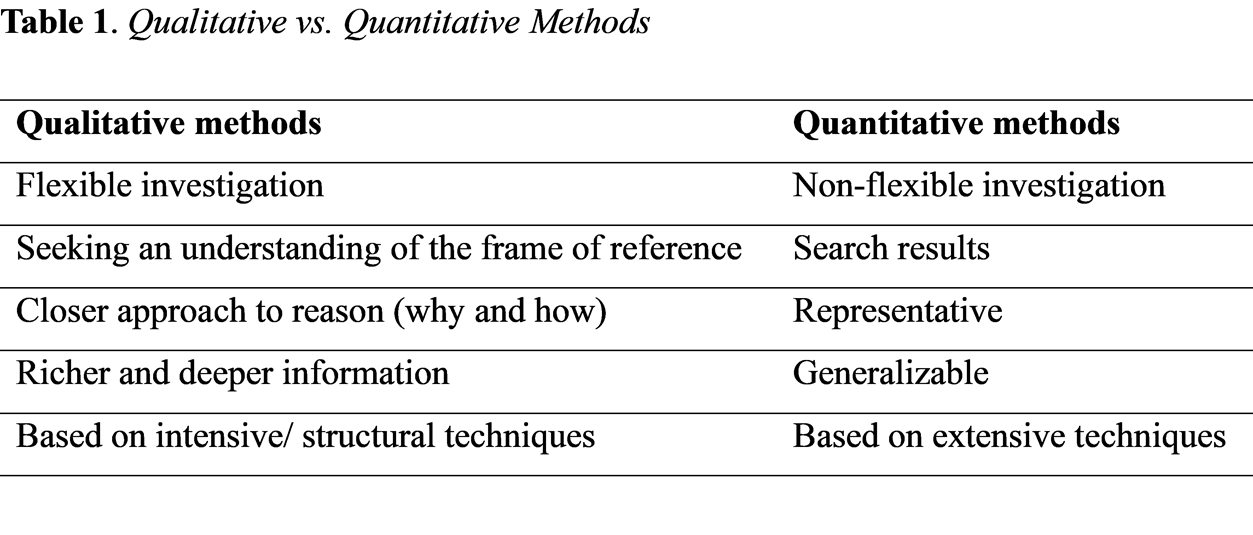

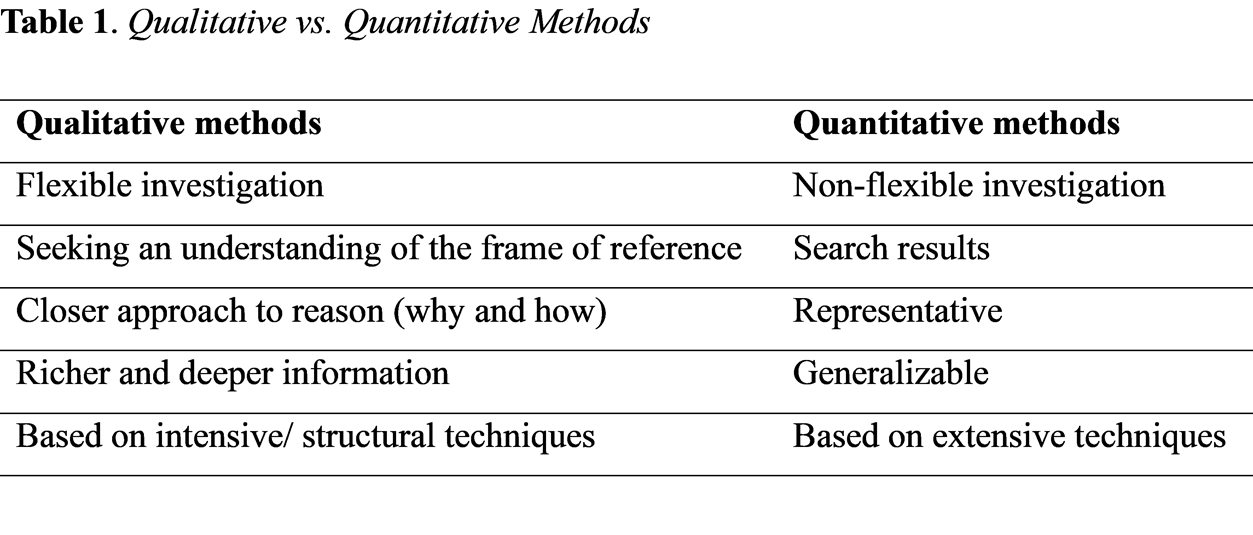

Quantitative research designs are more prevalent than qualitative research designs. Quantitative designs are structured, tested for validity and reliability, and can be easily defined and replicated. They provide enough details about a study design to ensure it can be verified and trusted. However, good quantitative research requires combining quantitative and qualitative skills to ascertain the nature and extent of diversity and variation in a given phenomenon (Tab. 1.).

Quantitative and qualitative research methods are often perceived as distinct approaches, yet they exist on a continuum of research methodologies. Quantitative research tends to prioritize generalizability, reliability, and validity, whereas qualitative research emphasizes dependability, credibility, and confirmability. While both methodologies have inherent strengths and limitations, researchers must meticulously consider their research questions and context to determine which approach is most suitable for their research (Fryer et al., 2018).

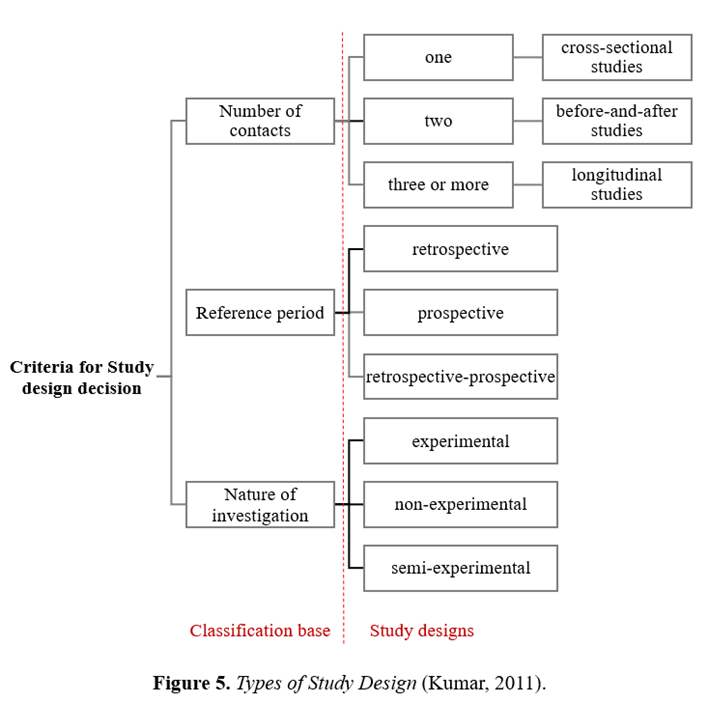

The qualitative-quantitative-qualitative approach to research is the most comprehensive and worth considering, involving starting with qualitative methods to determine diversity, using quantitative methods to quantify the spread, and then going back to qualitative methods to explain the observed patterns (Kumar, 2011). Quantitative studies use different types of designs that can be classified based on (1) the number of contacts with the study population, (2) the reference period of the study, and (3) the nature of the investigation.

1. Study designs based on the number of contacts

There are three study designs based on the number of contacts with the population: cross-sectional, before-and-after, and longitudinal studies. Cross-sectional studies are the most common and enable researchers to obtain an overall picture of a phenomenon or issue at one point in time. Before-and-after studies measure change in a phenomenon by comparing data collected before and after an intervention. Longitudinal studies study the pattern of change over time and involve multiple contacts with the study population. However, frequent contact with respondents may lead to the conditioning effect, where they respond with little thought or lose interest.

2. Study designs based on the reference period.

In research, the design of studies often centres around a specific reference period which examines a situation, event, problem, or phenomenon. There are two main types of studies - retrospective and prospective. Retrospective studies analyse past events using data collected from that time or people's memories, while prospective studies aim to predict future outcomes or the potential prevalence of a phenomenon. Experiments fall under the category of prospective studies, as the researcher has to wait for an intervention to impact the study population. Retrospective-prospective studies combine both approaches by examining past trends in a phenomenon and then tracking the study population to determine the impact of an intervention.

3. Study designs based on the nature of the investigation

Quantitative research designs can be categorized as experimental, non-experimental, quasi-, or semi-experimental based on the nature of the investigation (Cash et al., 2016; Miller et al., 2020; White & Sabarwal, 2014). The experimental study designs can be classified as follows:

- The after-only experimental design refers to a scenario where the researcher intends to study the impact of an intervention on a population that is being or has been exposed to the intervention. In this case, the change in the dependent variable is measured by comparing the "before" (baseline) and "after" data sets. However, this design needs to be revised as it does not provide a proper baseline for comparison, and the two data sets are not comparable. Some of the changes in the dependent variable may be due to differences in how the data sets were compiled.

- The before-and-after experimental design overcomes the problem of retrospectively constructing the "before" observation by establishing it before introducing the intervention to the study population. While this design addresses the comparability issue of the after-only design, it does not necessarily attribute any change to the intervention. To address this, a control group is introduced.

- In a study utilizing the control group design, the researcher selects two population groups, a control group and an experimental group, to be as comparable as possible except for the intervention. The "before" observations are made on both groups simultaneously, and the experimental group is exposed to the intervention. When it is assumed that the intervention has had an impact, an "after" observation is made on both groups and the difference in the dependent variable(s) between the groups is attributed to the intervention.

- The double-control design goes a step further than the control design in quantifying the impact attributed to extraneous variables. In this design, two control groups are used instead of one to separate other effects that may be due to the research instrument or respondents.

- In a comparative design, a study can be carried out either as an experiment or a non-experiment. In the comparative experimental design, the study population is divided into the same number of groups as the number of treatments to be tested. The baseline concerning the dependent variable is established for each group, and the different treatment models are introduced to the other groups. After a certain period, when the treatment models have had their effect, the "after" observation is carried out to ascertain any change in the dependent variable. The study compares the effectiveness of interventions by analysing the degree of change in the dependent variable among different population groups.

- In a matched control experimental design, comparability is determined individually-by-individually. Two individuals from the study population who are almost identical concerning a selected characteristic and condition are matched and allocated to a separate group. Once the groups are formed, the researcher decides which group is to be considered control and which experimental.

- A placebo design attempts to determine the extent of the placebo effect, a patient's belief that they are receiving treatment, even if it is ineffective. In this design, two or three groups are used, depending on whether or not the researcher wants to have a control group.

- Two groups are formed in the cross-over comparative experimental design, also known as the ABAB design, and the intervention is introduced to one of them. After a certain period, the impact of this intervention is measured, and the interventions are crossed over.

Numerous researchers take a pragmatic approach to their research and utilize quantitative methods to investigate extensive data sets, test hypotheses or examine subjects that can be quantified. Nevertheless, selecting the appropriate research design and data collection instruments is more fundamental than using the proper data analysis tools. This remains a critical component of all research, regardless of its quantitative or qualitative nature (Sukamolson, 2007).

Despite the inherent challenges in measuring qualitative information, we can still glean meaningful insights by utilizing specialized research tools designed to convert attitudes, beliefs, and other intangible concepts into quantifiable data. This approach enables us to investigate various phenomena using quantitative methods, providing valuable insights into the complexities of human behaviour and experience.

Grimes & Schulz (2002) formulated a comprehensive framework of alternative research methodologies that researchers can employ when selecting an appropriate approach for their study, depending on their research question and the challenges inherent in their research design (Fig. 2).