Researchers use narrative analysis to gain insight into how research participants construct stories and narratives based on their personal experience. People give meaning to their lives through the stories they tell, and their stories help to shape other people’s lives. The goal of narrative analysis is to transform prople’s individual narratives into data that can be coded and organised so that researchers can easily understand the impact of a certain event, feeling, or decision on the involved people, i.e. they can reveal how humans experience their world (Connelly and Clandinin, 1990, p. 1). The result of the narrative analysis is a core narrative of experience. This process involves a two-stage interpretation process (Fig. 3). First, the research participants themselves interpret their own lives through the narrative they create. Then, the researcher interprets the participants’ narratives.

Narratives can be obtained from various sources, such as journals, letters, conversation, autobiographies, transcripts of in-depth interviews, focus groups, or other forms of qualitative research. These narratives can be individual or collective, and pertain to various life aspects, such as experiences, identities, values, attitudes, or social contexts. Narratives serve as the basic units for exploring and interpreting a phenomenon or problem.

The analysis of narratives typically involves several steps. The first step is collecting narratives or stories from relevant individuals or groups. After collecting the narratives, the next step is coding or categorizing. This entails identifying key themes, patterns, or elements that emerge from the narratives. Coding can be qualitative, where researchers manually identify and categorize key elements, or quantitative, where computer programmes are used to analyse large datasets. Coding is followed by the analysis and interpretation. Researchers analyse the collected narratives to identify relationships, contradictions, trends, or deeper meanings that can be extracted from the stories. This phase may also involve linking the narratives to a theoretical framework or conceptual model to gain a deeper understanding of the phenomenon under study.

The narrative methodology provides contextually rich and in-depth information about individual or group experiences, perspectives, and identities. It also allows researchers to explore subjective experiences, and get first-hand information on the complexity of human life. However, it is important to be aware that the narrative methodology has its limitations, such as the subjectivity of the collected stories, the possibility of selective reporting, or the researcher’s biased interpretations.

Narrative analysis offers valuable insights into the lived experiences of individuals and groups, shedding light on their perspectives, beliefs, and social contexts. According to Bruner (1990), the primary way individuals make sense of experience is by casting it in the narrative form, which is especially true of difficult life transitions and trauma. Researchers must respect informants’ ways of constructing meaning, and analyse how it is accomplished, because their stories do not mirror the world, but are creatively authored, rhetorical, replete with assumptions, and interpretive (Reissman, 1993, p. 5). So, narrative analysis has to do with ‘how protagonists interpret things’ (Bruner, 1990, p. 51), whereas the researcher systematically interprets their interpretations. Investigators do not have direct access to another’s experience, but have to deal with its representations – text, talk, interaction and interpretation, which are impossible to be neutral and objective. So, in telling about an experience, there is inevitably a gap between the experience as one lived it and any communication about it. How a story will be told depends on the listeners, too. Narratives are inevitably self-representations. However, individual narratives also reveal a lot about the social life, making it possible to examine gender inequalities, racial oppression, and other practices of power that may be taken for granted by individual speakers (Reissman, 1993, p. 5).

Narratives are usually taped and then transcribed for the purpose of research. Transcribing discourse is not easy, and there is always a dilemma as to how detailed transcriptions should be, how they could best capture the rhythm of one’s talk, if they should include silences, false starters, discourse markers, etc., and it can be said that there is no single, true representation of the spoken language, whereas the choices as to what to include and how to arrange the text have serious implications for how a reader will understand the narrative (Reissman, 1993, p. 13). Then, the researcher analyses the transcript, edits, and reshapes what was told, creating a hybrid story, influenced by their values and theoretical commitments. Then the text reaches readers, and each text is open to several readings and constructions, even for the same reader, but in different historical contexts (Reissman, 1993, p. 14). Therefore, theoretical levels of abstraction or generalisation are difficult to reach when working with personal naratives, which require comparative work (Reissman, 1993, p. 70). Instead, the aim is to offer insights into how a given person, in a given context, makes sense of a given situation., i.e. to produce an account of lived experience in its own terms rather than one prescribed by pre-existing theoretical preconceptions (Smith & Osborne, 2015, p. 53).

Narrative analysis emphasizes the importance of researchers’ being prepared for unexpected consequences, and taking appropriate action when they arise during the research process (Smythe & Murray, 2000). This evolving approach of the narrative methodology contributes to the development of knowledge in a meaningful and sustainable way, informing future practices on socially significant issues (Bruce et al., 2016). What makes the narrative research unique is its emergent design, which involves evolving from data collection to analysis, and generating new knowledge through inductive reasoning from participants' accounts (Bruce et al., 2016). In narrative analysis, how a story is told is as important as what is said in order to understand the psychological and social life.

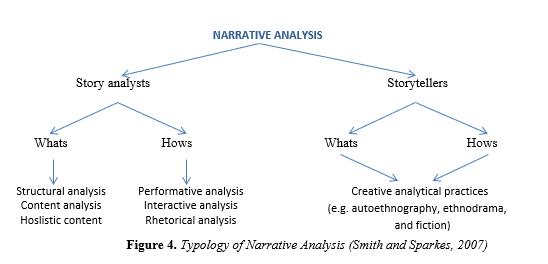

There are many different types of the narrative analysis. Smith and Sparkes (2007) introduced a typology (Figure 4):

Within this typology, two contrasting viewpoints on the narrative analysis (the storyteller and the story analyst) are illuminated, along with three specific methods (structural, performative, and autoethnographic creative analytic practices) that each viewpoint can employ to analyse the content and characteristics of stories. Story analysts are the researchers who conduct narrative analysis by stepping outside from the story, and using analytical procedures, strategies and techniques in order to abstractly analyse, explain and think about its certain features, theorising it from a disciplinary perspective. On the other hand, storytellers move away from abstract theorising and explaining towards the goal of intimate involvement, engagement and embodied participation with stories. For them, stories are analytical, because when telling stories, people employ analytic techniques to interpret their words (Smith & Sparkes, 2007, p. 21).