The "Statement of the Problem" is a critical introduction component. It briefly describes the research gap or problem your study aims to address. A well-articulated problem statement offers the reader a clear understanding of what the study seeks to resolve and provides a framework for setting your research objectives and questions (Creswell & Creswell, 2017). It is essential to ensure that the problem is neither too broad nor too narrow; both extremes can make the study less impactful (Ellis & Levy, 2008).

Here is an example of problem statement from “Driscoll, D. L. (2011). Connected, disconnected, or uncertain: student attitudes about future writing contexts and perceptions of transfer from first year writing to the disciplines. Across the Disciplines, 8(2).”:

This article begins by providing a review of relevant research concerning transfer of writing knowledge, theories of transfer, and issues related to motivation and perceived course value. Next, the article discusses the method of inquiry and context for the study. Results from the study are followed by a discussion of findings. The article closes by presenting teaching strategies and techniques to facilitate the transfer of writing knowledge both in FYC and in disciplinary writing contexts. As this study will demonstrate, the attitudes that students bring with them about writing impact their perceptions of the transferability of writing knowledge; because we know transfer of learning is an "active" process, these attitudes may be detrimental to their ability to learn and effectively use prior writing knowledge in disciplinary courses (Driscoll, 2011, p. 2).

Students' Difficulty with Transfer Across the Disciplines Evidence for the complexity of writing transfer in FYC and across the disciplines is evident in the work done by Herrington (1984), McCarthy (1987), Walvoord and McCarthy (1990), Beaufort (2007), Bergmann and Zepernick (2007), and Wardle (2007). Nearly all of the research on writing transfer indicates that if students fail to recognize similar features in diverse writing contexts and tasks, then the transfer of writing skills will most likely be unsuccessful. Although students often have been taught writing processes and skills that would assist them throughout their educational careers, these studies show that they are often unable to draw upon that knowledge and instead perceive each situation as entirely new and foreign. In her qualitative examination of the writing in two college chemistry courses, Herrington (1984) found that students believed that the writing tasks and required skills in each course were very different despite the many similarities Herrington found between the tasks (p. 331). Herrington also discovered that each course represented a unique learning situation where students needed to learn how to adapt their prior knowledge in order to be successful (Driscoll, 2011, p. 2).

As you can see from the example above, after drawing the main framework and explaining main concepts Driscoll (2011) created separate sub-heading as “Students’ Difficulty with Transfer Across the disciplines” in her introduction section. In this article she tried to explore connections between theories of student attitudes and motivation with theories of transfer to investigate their relationship. Thus, she tried to clarify what she has done and to addressing the gap the study’s filled by explaining students’ current writing transfer problems according to main studies in literature.

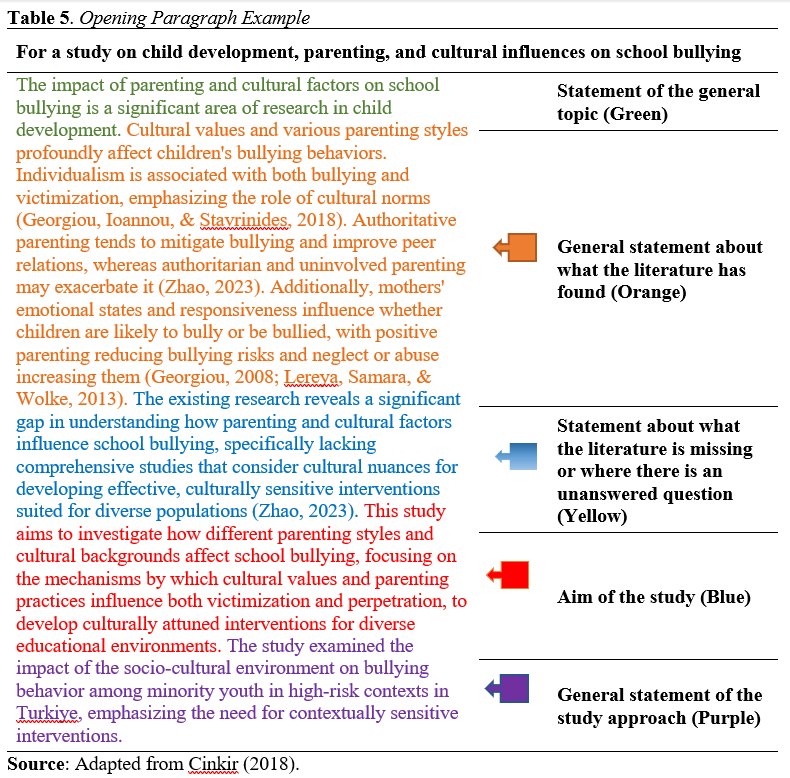

The below table shows how to organize the structure of an opening paragraph according to the themes of the “general topic”, “what the literature has found”, “missing aspects or unanswered questions”, “the aim of the study”, and “the study approach”. By structuring the information in this way, it clarifies the purpose, findings, gaps, and aims of the study within the broader context of the research on bullying, parenting, and cultural influences.

In summary, when stating the problem, it is important to pay attention to how wide or narrow the impact area of the study is. For example, information and theories synthesized from existing literature can form the framework of the research. Research can reveal the complexity of the problem, and this claim can be based on data compiled from other studies. The study contributes to this gap in the literature by aiming to investigate the relationship between the variables subject to research.